- • Trump 2020 app uses data to sidestep online platforms

- • Biden app accesses phone contacts to build ‘relational organizing’

- • Trump inspiration appears to come from India’s Narendra Modi

Ahead of President Trump’s rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, his 2020 re-election campaign manager Brad Parscale tweeted about the event. “Just passed 800,000 tickets,” he wrote. “Biggest data haul and rally signup of all time by 10x. Saturday is going to be amazing!”

Parscale’s numbers for the rally—originally scheduled for Juneteenth and still set to occur just miles from the site of one of American history’s deadliest acts of racial violence—have come in for criticism after only 6,200 people actually turned up, with sign-up numbers supposedly inflated by pranking teens and K-pop fans. But even on the surface, his claim was confusing: the venue holds only 19,000 people. So what was the campaign doing signing up so many people for tickets?

The clue lies in Parscale’s use of the phrase “data haul.”

Data collection and targeted online messaging were integral to the 2016 US presidential election, and they will be again in 2020. But there has been a shift. In the same way that candidates in the last cycle used Facebook to reach and persuade voters, ongoing research from our team at the propaganda research lab at UT Austin’s Center for Media Engagement suggests that 2020 will be defined by the use of bespoke campaign apps. Purpose-built applications distributed through the App Store and Google Play Store allow the Trump and Biden teams to speak directly to likely voters. They also allow them to collect massive amounts of user data without needing to rely on major social-media platforms or expose themselves to fact-checker oversight of particularly divisive or deceptive messaging.

Trump 2020: A data-hungry channel for disproven claims

The Official Trump 2020 app, which has been downloaded approximately 780,000 times according to the measurement service Apptopia, launched in mid-April.

The app has “News” and “Social” tabs offering carefully selected feeds of tweets and articles that reinforce the campaign’s talking points, often actively deceiving readers with highly questionable or entirely disproveninformation under headlines such as “Media Continue to Spread Debunked Theory About Tear Gas,” “Media Mask-Shamers Keep Getting Caught Breaking Their Own Rules,” or “Top 8 Moments from Joe Biden’s Embarrassingly Disastrous, Epically Boring Livestream.” Most messages, articles, and announcements inside the Trump app have no named author; they rarely cite sources beyond government press releases and tweets from Trump’s own supporters and White House staff. The app also has campaign releases that attack social-media companies like Twitter and Snapchat, berating them for perceived bias and lack of transparency on one hand while adopting opaque and attention-driven strategies themselves.

Users are required to provide their phone number full name, email address, and zip code. The campaign intends to collect the cell-phone numbers of 40 to 50 million voters.

Data collection—as Parscale’s comment suggested—is perhaps the most powerful thing the Trump 2020 app does. On signing up, users are required to provide a phone number for a verification code, as well as their full name, email address, and zip code. They are also highly encouraged to share the app with their existing contacts. This is part of a campaign strategy for reaching the 40 to 50 million citizens expected to vote for Trump’s reelection: to put it bluntly, the campaign says it intends to collect every single one of these voters’ cell-phone numbers. This strategy means the app also makes extensive permission requests, asking for access to location data, phone identity, and control over the handset’s Bluetooth function.

The app has already received some criticism, not least from security researchers who found it had left information exposed that could allow hackers to access the user data. The response to this made the campaign’s priorities clear: they rapidly fixed the bug once it had been disclosed, but still maximized the data they themselves could collect. They want as much voter data as possible, even if they don’t want it left vulnerable to outsiders—and will use it in any way they see fit.

A member of our research team discovered that the app was compiled with an older version of Android, which does not include some of the latest privacy improvements, and uses software provided by a company called Phunware, well known for collecting people’s location information and relations with the Trump campaign, a role highlighted by a Wall Street Journal investigation last year. Phunware has come under major scrutiny recently for accepting millions of dollars in federal loans intended to help small businesses cope with the coronavirus, and in May Nasdaq filed paperwork with the Securities and Exchange Commission to delist the company over its finances. Phunware’s invasive tactics for gathering data and reaching voters have drawn comparisons to Cambridge Analytica.

Team Joe: Your contacts are critical

Team Joe, the app put together by Joe Biden’s campaign, has some surface similarities to the Trump app, but it is a very different proposition. It does some things that the Trump app does, including sending users notifications of upcoming campaign events or training sessions for digital activists. But where the Trump app has range of uses, from spreading tailored campaign messages to airing live streams of rallies, Team Joe is largely built for a single purpose: relational organizing. This concept is spelled out in the Team Joe Digital Tool Kit:

“Relational organizing is when volunteers leverage their existing networks and relationships in support of our candidate, Joe Biden. Friend-to-friend contact is one of the most effective methods for having meaningful conversations about our campaign, and it is an efficient way to persuade and identify supporters … We are calling voters and caucusgoers to identify supporters and persuade friends and family to support Joe. These conversations with targeted voters and caucusgoers to increase support will make a big difference in electing Vice President Biden.”

Practically, this means that when you download the app you are prompted to share your contact list, which is then cross-referenced with the party’s voter files. The system identifies people you may have a personal connection with who might be persuaded to vote for Biden. From there, it prompts you to send these potentially undecided folks personalized messages.

One organizer explains how this works during a Joe Biden Action Center app orientation:

“Conversations that you have with friends or family are always a little more meaningful. And sometimes, if I’m calling a voter, they might have gone through something very traumatic, like a really bad hospitalization that they might not want to talk about with a random volunteer … but they might talk to you about ‘Oh, yeah. I had cancer and it was terrible but the Affordable Care Act, Obamacare, really helped me in that process.’ So if you do want to help us do that you can text App to 30330, or if you don’t wanna do that you can just go to joe.link/app.”

Relational organizing is a nuanced version of data targeting. Its principles are not new—both Obama presidential campaigns heavily relied on it—but like many political communication strategies, it has consequences that change with scale, advanced data analytics, and automation. The Biden app uses advanced data parsing practices but is not exactly automated. It blurs the line between the personal and the political.

With relational organizing, the Team Joe app blurs the line between the personal and the political.

Our ongoing research—which is mostly qualitative and involves interviews with tech makers, political marketers, and campaign members—has revealed that data-driven relational organizing is becoming the go-to outreach strategy for US political campaigns. Interviewees extol the virtues of highly personalized text messages sent by volunteers, a practice fine-tuned by the Bernie Sanders campaign. This and similar forms of relational organizing are already the norm in Mexico and Latin America, where they are used not to increase civic engagement but instead by mass manipulators seeking to adapt to the increased scrutiny of bots and sock-puppet accounts. A prominent Mexican journalist elaborated on this in a recent interview with us:

“Well, in Latin America and in Mexico we don’t use bots or software. It was left behind a few years ago because it was really easy to detect on Twitter or Facebook and by researchers like me … we are entering an era of war propaganda, and I think that’s where the trend is headed.”

What they want from you

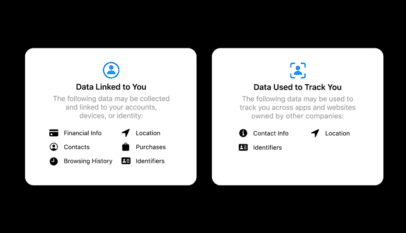

If you want to understand what the Trump and Biden apps are really for, compare the permissions requested in the Google Play Store. Besides some basic network and notification permissions, the Team Joe Campaign App may ask for access to your contacts. The Official Trump 2020 App has a much longer list of access requests. It wants to read your contacts and know your precise and approximate location (GPS and network based). It requests the ability to read your phone status and identity (a vague permission that sometimes gives access to unique device numbers), pair with Bluetooth devices (such as geolocation beacons), and perhaps read, write, or delete from SD cards in the device.

The use of Bluetooth is especially notable because it can capture data and target people with political messages as they travel through a physical space. This practice has jumped to politics from the advertising industry. In one recent example, Bluetooth beacons (the radio transmitters used to track cell-phone users via Bluetooth signals) were found in campaign yard signs. In another, people were surveilled using these practices when they went to church. Our team has been exploring how this phenomenon—which we term geo-propaganda—has increased.

As you walk past a beacon…