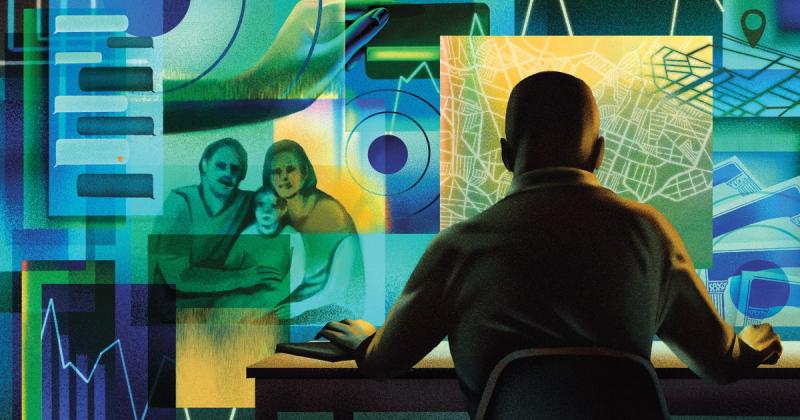

Identity theft can have devastating effects. In one recent example, a retired couple in the Chicago suburbs came within hours of losing their life savings to a sophisticated attack.

The attackers worked for months to gain access to the couple’s retirement accounts. After obtaining one of the individuals’ Social Security numbers from a prior data breach, the attackers contacted the couple’s cellphone company, impersonated one of them, and then diverted text messages and calls to the attackers’ cellphone to intercept multi-factor authentication codes from the couple’s bank. With help from privacy professionals, the couple was able to recognize the cloning attack and immediately contacted the cellphone carrier and the banks. It was a Friday afternoon, and the attackers had placed an order to sweep the couple’s life savings into a separate account first thing on Monday morning. The couple was able to get the transfer order canceled, but they came within 72 hours of losing much of their retirement savings.

Financial and identity theft is just one of the many dangers of personal information falling into the wrong hands. Location data from your cellphone, even when anonymized, can reveal personally identifiable information that could be used for surveillance, and scammers can piece together bits of information from social media accounts to do online phishing.

Technology has made life undeniably more convenient. But how much has this convenience put our privacy and personal information in peril?

“We’re all generating an exponential amount of data all the time,” says Caitlin Davitt Fennessy ’04, vice president and chief knowledge officer at the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP). The abundance of personal information — and the ability to connect the dots between those bits of data — is cause for concern.

“Anything that allows data to be collated and well organized turns a few incidental web searches here and a few purchases there into knowledge about your personal life that would otherwise be very difficult to obtain,” says professor Matthew Kugler, who teaches a popular course on privacy law at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law. “If someone put your TikTok history next to your Amazon history next to your Google history, they might be able to learn a lot about you that you didn’t mean to tell them.

“And if I give an app data…