Google’s push to become a privacy-positive company over the past year has been, depending on how you look at it, an act of genuine benevolence, a brilliant marketing decision, or straight-up bullshit. So when Google CEO Sundar Pichai announced the company’s latest moves in the privacy-protecting space on Twitter yesterday, the biggest surprise—at least to me—was the lack ofskepticism I was seeing from other reporters in the privacy and policy spaces.

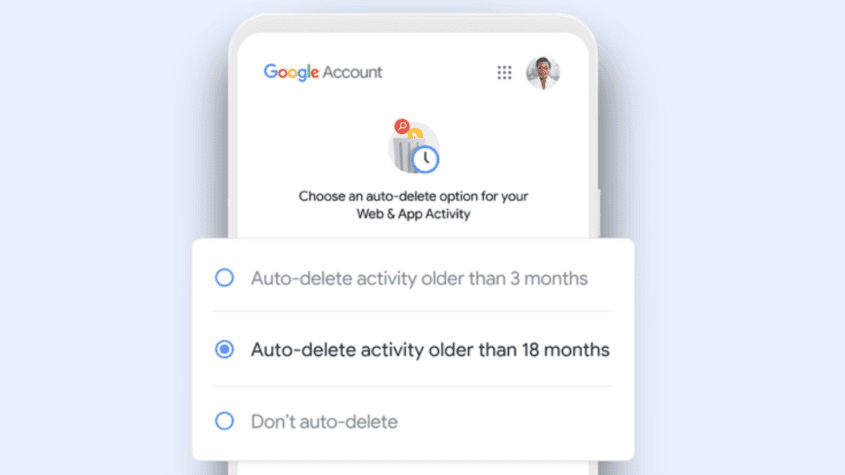

In short: The update, as described in Pichai’s initial tweet and in a blog postregarding the rollout, broadly changes the way the company retains user data—not only making it easier to delete data, but also changing the default settings for new Google accounts so that this data auto-deletes by default every 18 months. (Existing users will have to seek out these settings and turn them on, though Pichai writes that Google will send reminders to existing users about these features.)

“We believe that products should keep your information for only as long as it’s useful and helpful to you,” he explains in the blog. “We continue to challenge ourselves to do more with less, and today we’re changing our data retention practices to make auto-delete the default for our core activity settings.”

It’s an idea that sounds great, in theory—after all, as the recent round of protests starkly reminded us, you can never be too careful about what digital breadcrumbs you might be inadvertently scattering around the web. Getting a new set of data from Google can, in theory, be kind of like getting a new digital identity—and with every refresh, Google’s giving you the chance to leave all of the old trackers and targeting tech behind.

But if you dig a little deeper, it quickly becomes clear that that’s not how digital data works at all—and that just like every other Google-led ploy for privacy, this latest update is about market power and not much else.

First, let’s get the specs on the update out of the way. To quote Pichai’s blog post directly:

Starting today, the first time you turn on Location History—which is off by default—your auto-delete option will be set to 18 months by default. Web & App Activity auto-delete will also default to 18 months for new accounts. This means your activity data will be automatically and continuously deleted after 18 months, rather than kept until you choose to delete it. You can always turn these settings off or change your auto-delete option.

He goes on to say that if a user wants to strip their details more frequently, they can set up an auto-delete for every 3 months. The option to turn on auto-deletions like these aren’t new, per se—the company actually rolled out this option just over a year ago, to fanfare similar to what we’re seeing with this new update.

The thing is—at least in the context of digital ads—your data is, by design, impossible to retroactively delete. Here’s an example: A while back, I downloaded an app that I later found to be sharing my prescription data with a few third parties, including Google. That data came packaged with so-called “anonymous identifiers” like my phone’s unique ad ID—a chunk of software that Apple and Google bake into their respective hardware.

If I try to wipe any activity—say, my prescriptions—from the app using the tools Google provides here, that doesn’t wipe that same intel from those third parties: They still have the data they’ve already collected on any relevant past activity. In my case, my prescription information is out there—not connected to me by name, sure, but it’s close enough. Because an activity or history-wipe doesn’t also wipe those anonymous identifiers I mentioned before, the minute I log back into that app to order a refill on some medication, a third party can see that, even though my Google account might be “wiped clean,” I’m still the same consumer that I was before.

Put another way, this kind of third-party jig directly ties my old, sullied Google account to my new, clean one—not just in this particular app, but in every app I might open on my phone, or every site that I browse on my laptop. And when those two accounts are tied across more of my apps that I’m using, or more sites that I’m surfing, I’ll quickly end up back in the same targeted hell I was trying to escape by taking Google’s offer of a shiny new account.

Not only that…

These Companies Know When You’re Pregnant—And They’re Not Keeping It Secret

In early 2012, the New York Times Magazine put out a cover story about Andrew Pole, a stat…