I. The Striking Difference Between Schrems I and Schrems II

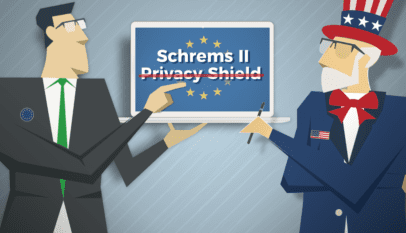

It would be misleading to view last week’s Schrems II[1] decision as only having an effect similar to that of the Schrems I[2] decision in 2015. While Schrems I invalidated the EU-US Safe Harbor treaty for cross-Atlantic data transfer, organisations still believed that they could rely solely on Standard Contractual Clauses (“SCC”s) to transfer data internally and externally. In effect, after the Schrems II decision, not only was the successor Privacy Shield treaty for cross-Atlantic data transfer invalidated, but data controllers, processors and supervisory authorities must now take immediate steps to satisfy new obligations which exceed the capability of SCCs to address.

As an immediate result of the Schrems II decision, parties may no longer rely on SCCs per se for the lawful transfer of personal data to any country for which the EU Commission has not issued an adequacy decision under GDPR Article 46. Note that this means nearly every non-EU country in the world, including the US. To date, just twelve countries have received adequacy decisions: Andorra, Argentina, Canada (for commercial organisations), Faroe Islands, Guernsey, Israel, Isle of Man, Japan, Jersey, New Zealand, Switzerland, or Uruguay.[3]

In Schrems II, the CJEU[4] highlights the requirement in GDPR Recital 108 that:

“…in the absence of an adequacy decision, the appropriate safeguards to be taken by the controller or processor in accordance with Article 46(1) of the regulation must ‘compensate for the lack of data protection in a third country’ in order to ‘ensure compliance with data protection requirements and the rights of the data subjects appropriate to processing within the Union.”[5]

The importance of providing appropriate safeguards is highlighted in over twenty references in Schrems II.[6] For data transfers to be lawful to countries other than the twelve listed above, Schrems II says “it may prove necessary to supplement the guarantees contained in [SCCs]”[7] with appropriate safeguards in the form of “supplementary measures,”[8] “additional safeguards,”[9] and “effective mechanisms,”[10] because (in the words of the court) SCCs “are not capable of binding the authorities of that third country, since they are not party to the contract.”[11] Since no grace period was announced for compliance with the CJEU decision in Schrems II, companies relying on the EU–U.S. Privacy Shield for data transfers should swiftly implement appropriate safeguards and mechanisms to avoid the risk of having data flows suspended, as the potential costs far exceed any possible, and possibly contemporaneous, fines.

Schrems II creates immediate, potentially highly disruptive obligations in the global data ecosystem. For example, without appropriate safeguards to adequately supplement the protection of SCCs to prevent the misuse of data:

- Data controllers and recipients of personal data must verify that the legislation of the destination country enables the recipient to comply with the GDPR before transferring personal data to that third country, and ongoing responsibility to monitor legislative changes that would invalidate that verification ;[12]

- Data controllers are obligated to terminate contracts with international recipients of personal data and return or destroy any data that has already been transferred, or be in breach of obligations under the GDPR and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights entitling data subjects to compensation for any damages suffered;[13]

- Data controllers, processors and supervisory authorities must block the transfer of personal data where country legislation is or becomes deficient.[14]

II. Safeguards Must Technologically (NOT Just Contractually) Prevent Misuse of Data

Before the GDPR, private sector data collection was limited principally to the collection by parties with whom a data subject had knowingly decided to conduct business and whom the data subject had agreed to trust. If a party violated the trust of a data subject, they could simply cease doing business with the party. However, the proverbial pendulum has now swung too far to one side – massive amounts of readily available data is “out there” on all of us, being used for purposes beyond our intentions, and without our awareness[15]or control.[16] Appropriate safeguards that technically obfuscate linkages between and among data elements while still retaining the utility of data – if combined with appropriate policies – can facilitate privacy protection while enabling ongoing (and robust) data usage.

The GDPR, and other modern data protection laws, implicitly acknowledge the proliferation of powerful technical tools performing analysis on massive stores of personal data. They also recognise the inability of policies or contracts – by themselves – to protect individual privacy rights. When confronted with these types of technologies, laws must balance them against the rights of data subjects while not stopping innovation.

Policy-based mechanisms, like SCCs, need complementary tools, like appropriate technical safeguards for data, to be effective. Policy tools can provide clarity as to particular actions that involve wrongdoing or inappropriate use of data. However, policy-based remedies – by themselves – will be “too little, too late” if data subjects suffer identity theft, loss of credit, denial of time-sensitive services, discrimination, etc. In circumstances where data subjects suffer these harms, there is no adequate remedy by policy alone. As noted in the article, Personal Data v. Big Data in the EU: Control Lost, Discrimination Found:

“As the Big Data age is here to stay, both law and technology must together reinforce, in the future, the beneficent use of Big Data, to promote the public good, but also, people’s control on their personal data, the foundation of their individual right to privacy”.[17]

Legal experts have…