Do you trust companies like Facebook to accurately and completely tell you how, and to what extent, their apps monitor and track you both on your phone and across the entire internet? The question is not a rhetorical one, as Apple’s latest privacy push relies on the answer to that question being “yes.”

Most privacy policies are an unintelligible mess. This problem, thoroughly documented by the New York Times Privacy Project in 2019, is only compounded when people are forced to read the sprawling documents on their smartphones — squinting the entire time they scroll. Apple unveiled a new feature on Monday for the forthcoming iOS 14 intended to address this problem. The proposed solution is labels, similar to nutrition labels seen on the side of food packaging, that quickly and clearly tell users how an app uses their data.

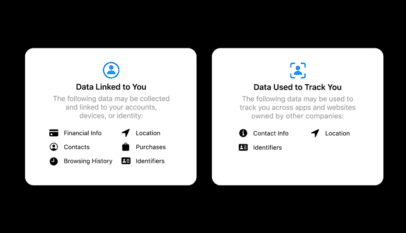

At face value, this idea sounds great. According to slides shared at WWDC, app labels would list out, in plain language, what data is linked to you and what data is used to track you. There’s just one glaring problem: All the information in the label is self-reported by the companies and developers behind the apps.

Katie Skinner, Apple’s manager of user privacy software, explained the company’s approach to the privacy labels during the WWDC presentation.

“We’ll show you what they tell us,” she noted. “You can see if the developer is collecting a little bit of data on you, or a lot of data, or if they’re sharing data with other companies to track you, and much more.”

Erik Neuenschwander, Apple’s director of user privacy, detailed how this differs from Apple’s current practices and how the company’s plan was inspired by the humble nutrition label (this all begins around 58:22 in the above embedded video if you want to watch along).

Today, we require that apps have a privacy policy. Wouldn’t it be great to even more quickly and easily see a summary of an app’s privacy practices before you download it? Now, where have we seen something like that before? For food, you have nutrition labels; you can see if it’s packed with protein or loaded with sugar, or maybe both, all before you buy it. So we thought it would be great to have something similar for apps. We’re going to require each developer to self-report their practices.

This raises a lot of questions. For starters…

INNOVATION AND DATA PRIVACY ARE NOT NATURAL ENEMIES: INSIGHTS FROM KOREA’S EXPERIENCE

The following is a guest post to the FPF blog authored by Dr. Haksoo Ko, Professor at Seou…