Inthe past when you first studied a company, you tried to figure out how it might perform in the months, quarters, and years ahead. But right now in the crony capitalism era, where we continue to witness one-man operations exposing big names as frauds, we need to acknowledge whether companies that have become industry leaders, that have risen from nowhere, and that have posted stellar quarter after stellar quarter, might be cooking the books.

Short-sellers and whistleblowers have become necessary for maintaining law and order within markets, exposing various types of fraud from Ponzi schemes to dodgy accounting tricks. Short-selling gets a bad rap because you desire to profit from a company’s collapse, but if performed ethically and responsibly, it exposes blatant corruption, improves market efficiency, and discourages repeat offenders from trying to pull the oldest tricks in the book. Whistleblowers also have an inconvenient caveat: They should be hailed as superstars, yet they have a tough time after revealing their former company’s swindle.

Now more than ever, as investors we must take every short-sellers’ and whistleblowers’ claims into account as a company’s stock could go to zero after being exposed as a stone-cold fraud. We must create a fraud detection framework, replicating the processes of reliable short-sellers who excel in identifying common red flags while listening to any whistleblower who raises legitimate concerns.

At first, this may sound hard, but once you discover how the biggest frauds of the 21st century were unveiled, you’ll realize that avoiding deception is a lot easier than you previously thought.

Bernie Madoff’s $64.8 Billion Pyramid Scheme

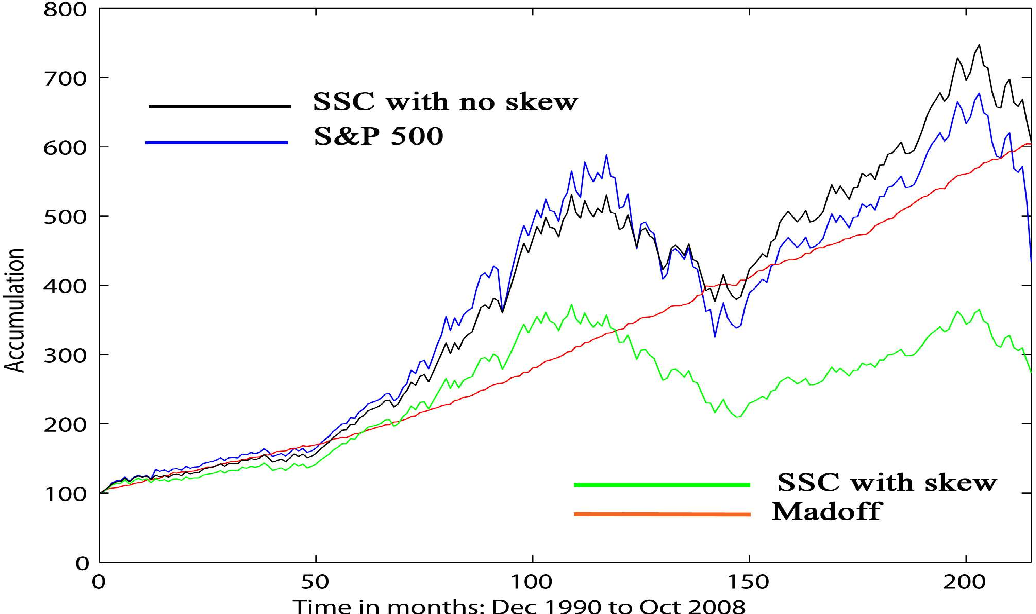

In 1999, Harry Markopolos caught wind of hedge fund manager Bernie Madoff making 1–2% returns each month consistently without fail.

As Markopolos worked as a portfolio manager at the time, he knew Madoff’s returns, which resembled a 45-degree line, had become too good to be true given the volatile nature of markets.

As Madoff’s Ponzi scheme grew, Markopolos sent ever-increasing amounts of incriminating evidence to the SEC in 2000, 2001, and 2005, but each time, the commission ignored it. “Hundreds, if not a few thousand people knew. They knew something was wrong with Madoff and they stayed away from him,” he said in his book: No One Would Listen.

Though despite nine years of Markopolos trying to expose Madoff, it was his sons contacting the FBI in December 2008 that brought down the Pyramid scheme.

After the exposé, in an interview with the Guardian, Markopolos revealed how he knew Madoff’s business model was an obvious fraud. He needed to bend reality: “If there’s only $1bn of options in existence and he’s many times that size, unless you could change the laws of mathematics, I knew I had to be right.”

The collapse of Bernie Madoff Securities Ltd. highlights an uncomfortable but important truth: you can’t always trust the authorities to protect you from an obvious fraud especially if it’s too big to fail — say $65 billion.

Folli Follie’s Fake Asia Business

In 2017, fund manager Gabriel Grego and a friend sat down for dinner.

While discussing business, Grego’s friend revealed he was invested in Folli Follie, a Greek retail company, that continued to grow roughly 20% per annum. Grego was familiar with the name as he had bought shares in the company during the Greek crisis but sold his stake shortly thereafter.

After dinner, Grego decided to study Folli Follie’s latest fundamentals to see if the company was investment material. But during his analysis, he discovered multiple red flags revealing possible deception.

The company’s store locator promoted many stores that were nonexistent. It claimed to have a digital presence similar to its competitors, yet it had 80% fewer website hits and was almost nonexistent on Google trends. Even Grego’s nearest Folli Follie store, which happened to be down the road from his manhattan office, turned out to be a different retailer that sold watches.

If that wasn’t enough, Grego visited Folli Follie’s Japanese stores and found that over 50% of them had either closed down or had started liquidating assets.

But the smoking gun came when he looked into the company’s auditors. Folli Follie claimed it was trying to cut costs by using a cheap accountancy firm, however, it was a relatively obscure entity with only two employees, no internet presence, and had only one client: Folli Follie.

Grego had collected enough evidence to expose Folli Follie, so he presented his findings via Kase Learning’s live stream. The stock fell 30% pre-market, the Greek authorities halted its listing, and the executives of Folli Follie were detained on criminal charges.

If you have time, watch his presentation at Kase Learning. It’s a fraud-exposing masterclass.

Enron’s $63 Billion Accounting Fraud

Over many years, Enron executives managed to orchestrate the biggest corporate fraud of all time.

As company revenue began to peak, multiple Enron executives along with their accounting firm, Arthur Andersen, helped cover up immense amounts of debt and toxic assets using hundreds of special purpose vehicles (SPVs) and special purpose entities (SPEs) to conceal losses and maintain the company’s growth narrative.

Enron based these shell companies on Tobashi schemes, using them to not only circumvent conventional accounting methods but to understate liabilities and overstate equity and earnings.

Over time, countless individuals inside and outside the company grew suspicious of Enron’s success from famed short-seller Jim Chanos to Enron employees unaware of what was really going on behind the scenes.

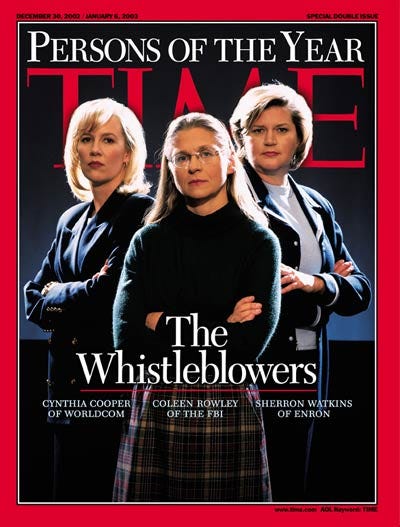

In the end, it was Enron’s then-Vice President of Corporate Development, Sherron Watkins, that blew the whistle, exposing the company’s accounting “irregularities”. Enron CEO Kenneth Lay — who was in on the scam — ignored Watkin’s memos and tried to fire her for exposing Enron’s fraud. But she went public five months later, revealing the biggest accounting fraud of all time.

Times magazine awarded Sherron Watkins with the “Person of the Year” award for courage and bravery.

The takeaway from the Enron scandal is even auditors, independent professionals hired to carry out an official inspection of an organization’s accounts, can not only fail to expose fraud but become part of it. It’s best not to rely on what they say about a company.

Oh! And Chanos made a whopping $500 million from his short position.

The Latest Scandal: Wirecard

Wirecard, Germany’s leading payment processing company, has been finally exposed as a fraud after multiple attempts from notable short-sellers and investigative journalists.

After years of the company’s top executives duping auditors, authorities, and shareholders, Philippino central bank governor, Benjamin Diokno, let the cat out of the bag, disputing that Wirecard had never deposited $2.1 billion into the Philippino financial system.

German authorities have arrested former-Wirecard CEO, Markus Braun, and the company has recently filed for bankruptcy. The Wirecard story is still developing and new information continues to be released about what went on behind the scenes.

The Wirecard scandal shows us that, even in 2020, fraud not only exists but thrives at the highest level.

10 Ways to Avoid Investing In Fraudulent Companies…

Understanding the Dutch Approach to GDPR Fines: Why Canadian Companies Need to Pay Attention

⚠️ IMPORTANT UPDATE This article accurately describes the Dutch AP’s pioneering…