The user experience of browsing the web is worse than ever. Even if you only spend a tiny amount of time online, it’s impossible to escape cookie consent notices. They’re the intrusive banners and blocks that appear each time you visit a new website that collects data about you through cookies. Each is asking the same question: will you allow this website to collect your information?

The spread of these cookie notices is down to European legislation. A combination of GDPR and how it altered the ePrivacy Directive forced pretty much every site on the web to ensure people in Europe clicked ‘allow’.

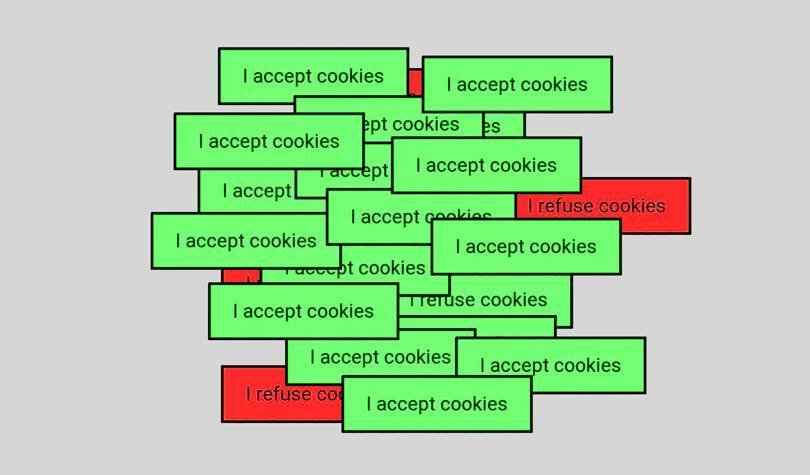

The legal changes were meant to make understanding web tracking easier for everyone. But two years after the arrival of GDPR, cookie consent notices are a blight on the web. Researchers have found that they use dark patterns to trick people into clicking ‘yes’, with a lack of enforcement against websites that don’t comply with the rules – and a general lack of awareness of what the cookie notices are meant to achieve – creating a real mess.

“Usually people click to get it away because it’s really big on the screen,” says Estelle Massé, a senior policy analyst and global data protection lead at non-profit internet advocacy group Access Now. “You want to move on. You don’t actually read what is happening, you don’t actually know what you’re consenting to. It’s not really helpful as a tool.”

Cookie notices come in all shapes and sizes – however, they largely work in the same way. They’re in place to ask people to provide their consent for the website they’re visiting to collect information about them. On your phone, laptop or tablet, cookies exist as strings of text that contain information. The cookies are stored by web browsers and communicated with the servers of a website each time it is accessed. Often cookies exist as identifiers – a code that’s unique to you.

The types of information websites collect through cookies depends on what they do – an online clothes shop will gather different information than a news website, for instance. Cookies can collect information that helps websites to function, such as those that detect spam and the servers that are being accessed, or other information that can lead to personalisation and targeted advertising. A website can detect the online identifiers given to you by Google or Facebook’s advertising infrastructure, helping to determine your interests based on your browsing history and present adverts that you may be more likely to click on.

The introduction of GDPR caused a huge spike in cookie consent notices across the web. The legislation changed the definition of consent within the ePrivacy Directive, which was created almost two decades ago to manage digital privacy, and ultimately made websites move to a cookie setup where a user has to click to say they allow cookies to be collected on their device. (Pre-ticked consent boxes do not count as a way to obtain consent for cookies, European courts have ruled).

According to research published in October 2019, following the adoption of GDPR more than 60 per cent of popular websites in Europe show cookie consent notices. Two of the authors behind the research, Christine Utz and Martin Degeling from Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany, say the percentage has likely increased since they completed their research and the detail that websites provide in cookie consent notices has improved.

Their research paper looked at the different positions of cookie notices on websites (people are most likely to interact with a notice in the lower left of the screen), the choices offered and the wording of notices. “Given a binary choice, more users are willing to accept tracking compared to mechanisms that require them to allow cookie use for each category or company individually,” the paper says. “We also show that the widespread practice of nudging has a large effect on the choices users make.”

Cookie consent notices can…

EU ruling: tracking-based advertising by Google, Microsoft, Amazon, X, across Europe has no legal basis

Landmark court decision against “TCF” consent pop ups on 80% of the internet 14 May 2025 (…