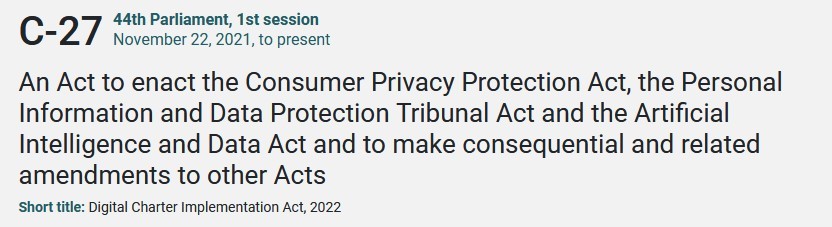

Note: this is the first in a series of blog posts on Bill C-27, also known as An Act to enact the Consumer Privacy Protection Act, the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act and the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act.

Bill C-27 is a revised version of the former Bill C-11 which died on the order paper just prior to the last federal election in 2021. The former Privacy Commissioner called Bill C-11 ‘a step backwards’ for privacy, and issued a series of recommendations for its reform. At the same time, industry was also critical of the Bill, arguing that it risked making the use of data for innovation too burdensome.

Bill C-27 takes steps to address the concerns of both privacy advocates and those from industry with a series of revisions, although there is much that is not changed from Bill C-11. Further, it adds an entirely new statute – the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA) – meant to govern some forms of artificial intelligence. This series of posts will assess a number of the changes found in Bill C-27. It will also consider the AIDA.

_________________________________

The federal government has made it clear that it considers consent to be a cornerstone of Canadian data protection law. They have done so in the Digital Charter, in Bill C-11 (the one about privacy), and in the recent reincarnation of data protection reform legislation in Bill C-27. On the one hand, consent is an important means by which individuals can exercise control over their personal information; on the other hand, it is widely recognized that the consent burden has become far too high for individuals who are confronted with long, complex and often impenetrable privacy policies at every turn. At the same time, organizations that see new and emerging uses for already-collected data seek to be relieved of the burden of obtaining fresh consents. The challenge in privacy law reform has therefore been to make consent meaningful, while at the same time reducing the consent burden and enabling greater use of data by private and public sector entities. Bill C-11 received considerable criticism for how it dealt with consent (see, for example, my post here, and the former Privacy Commissioner’s recommendations to improve consent in C-11 here). Consent is back, front and centre in Bill C-27, although with some important changes.

Section 15 of Bill C-27 reaffirms that consent is the default rule for collection, use or disclosure of personal information, although the statute creates a long list of exceptions to this general rule. One criticism of Bill C-11 was that it removed the definition of consent in s. 6.1 of PIPEDA, which provided that consent “is only valid if it is reasonable to expect that an individual to whom the organization’s activities are directed would understand the nature, purpose and consequences of the collection, use or disclosure of the personal information to which they are consenting.” Instead, Bill C-11 simply relied upon a list of information that must be provided to individuals prior to consent. Bill C-27’s compromise is found in the addition of a new s. 15(4) which requires that the information provided to individuals to obtain their consent must be “in plain language that an individual to whom the organization’s activities are directed would reasonably be expected to understand.” This has the added virtue of ensuring, for example, that privacy policies for products or services directed at youth or children must take into account the sophistication of their audience. The added language is not as exigent as s. 6.1 (for example, s. 6.1 requires an understanding of the nature, purpose and consequences of the collection, use and disclosure, while s. 15(4) requires only an understanding of the language used), so it is still a downgrading of consent from the existing law. It is, nevertheless, an improvement over Bill C-11.

A modified s. 15(5) and a new s. 15(6) also muddy the consent waters. Subsection 15(5) provides that consent must be express unless it is appropriate to imply consent. The exception to this general rule is the new subsection 15(6) which provides:

(6) It is not appropriate to rely on an individual’s implied consent if their personal information is collected or used for an activity described in subsection 18(2) or (3).

Subsections 18(2) and (3) list business activities for which personal data may be collected or used without an individual’s knowledge or consent. At first glance, it is unclear why it is necessary to provide that implied consent is inappropriate in such circumstances, since no consent is needed at all. However, because s. 18(1) sets out certain conditions criteria for collection without knowledge or consent, it is likely that the goal of s. 15(6) is to ensure that no organization circumvents the limited guardrails in s. 18(1) by relying instead on implied consent. The potential breadth of s. 18(3) (discussed below), combined with s. 2(3) makes it difficult to distinguish between the two, in which case, the cautious organization will comply with s. 18(3) rather than rely on implied consent in any event.

The list of business activities for which no knowledge or consent is required for the collection or use of personal information is…

Canada’s Privacy Landscape in 2026: A Gap in Strategy between the “Aspiration of Policy” and the “Reality of Business”

Year-End Evaluation for Business Owners By Derek Lackey, Managing Director, Newport Thomso…